Part 70: The Almoravid Offensive

Chapter 6 - The Almoravid Offensive - September 1826 to June 1828The offensive came out of nowhere, with the beaches of Valencia peaceful and serene one moment, and overrun with Berber ships the next. The Moroccans had complete naval supremacy in the Mediterranean, so the attack itself wasn’t very surprising - the astonishing part was the sheer size of the invasion, with over a hundred thousand Berbers somehow making the crossing and storming the shores of eastern Iberia in one fell swoop, leaving historians and enthusiasts dumbfounded to this very day.

Putting the logistics of a nineteenth century naval invasion aside, however, the Almoravid army launched into Iberia without delay or hesitation. The offensive was well-planned and decisive, with the Moroccans quickly capturing Balansiyyah and pushing westward, reaching Majrit within a month of their landing.

With the speed and ferocity of the invasion catching them off-guard, the Majlis al-Shura immediately descended into chaos, erupting into their typical bitter factional infighting. Grand Vizier Zulfiqar quickly took charge, however, postponing his planned crossing of the Gibraltar straits and recalling the army north. Almost forty first-rate warships were now patrolling the straits, anyways, so it would’ve been suicide to take them on just then.

The Majlisi Guard, half of which was commanded by Grand Vizier Raed and the other half by sheikh Fadhil al-Farihi, rushed northwards on a forced march, only halting once they reached the outskirts of Tulaytullah. The army then dug in around the city, with both the Grand Vizier and his marshals deciding against taking the fight to the Moroccans, instead devoting their resources to repelling any attempted invasions into al-Andalus proper.

And as they expected, it didn’t take very long for that to happen. The Berbers managed to surround and blockade Majrit, breaching and viciously sacking the small city after two weeks of heavy siege, reducing its fortifications to rubble. After imposing their control over Majrit, the army pushed southward, laying siege to Tulaytullah - which firmly within Andalusi borders.

Zulfiqar couldn’t just let the Almoravids capture such an important city, not without attempting to dislodge them, at the very least. Even so, acting on sheikh Fadhil’s advice, the Grand Vizier stalled in attacking the Almoravid army for as long as possible, hoping for the arrival of Tirruni reinforcements to bolster his own forces.

After three weeks of siege, however, the Berbers managed to force a small breach in the walls of Tulaytullah. And with so sign of reinforcements, Fadhil was finally forced to commit to battle, with the Andalusi and Moroccans clashing beneath the engraved walls of the City of Sultans just hours later.

Needless to say, with 170,000 men fighting it out under the sweltering sun of Iberia, the battle of Tulaytullah would count amongst the bloodiest in the Tirruni Wars.

As a whole, the Majlisi Guard was certainly better trained and armed than their foes, but the Almoravids cleverly concentrated their attacks on the Majlisi flanks - which were largely drawn from peasant militias, weak-willed cowards who fled at the first sight of African guns (or so sheikh Fadhil would later claim). It didn’t take long for the flanks to collapse, and with it, so did the hope of somehow defeating the Almoravid army.

So after an entire day of vicious fighting, the Andalusi withdrew in an orderly retreat, the hard ground beneath their feet greedily drinking up the blood of eighty thousand casualties.

Tactically, the Andalusi gave as good as they got, better even - but if the Moroccans had one thing in ample supply, it was bodies. More importantly, the Majlisi Guard had failed their strategic objective, which was to lift the siege of Tulaytullah. As it was, the Berbers were able to quickly surround the City of Sultans, with their artillery firing at its thick walls before the night was out.

When news of the defeat arrived at Qadis, the already-chaotic Majlis teetered on the edge of collapse, with half the assembly convinced that the Moroccans would march on them next. And that wasn’t the worst of it, with several high-ranking nobles sending their pawns to the Grand Vizier, demanding that their losses be reversed without hesitation.

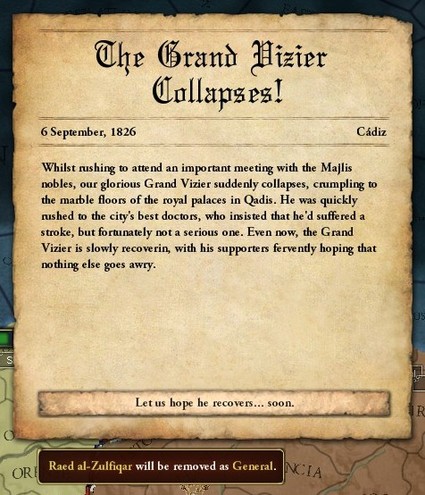

Already an old and tired man, forced to deal with endless anger and criticism, and living under the constant fear of assassination, the Grand Vizier finally snapped. Whilst receiving a scouting report, Raed suddenly collapsed onto the floor of his tents, with his aides and guardsmen rushing to his crumpled body.

His doctors would later say that Zulfiqar had suffered a minor stroke, not enough to paralyse him, but enough to force him to his bed. Rumours regarding the Grand Vizier’s mental health immediately began to spread, and partly in an attempt to dispel them, Raed gave orders to dipatch diplomats to Emperor Tirruni demanding immediate assistance.

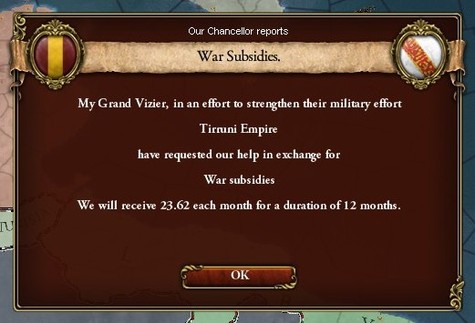

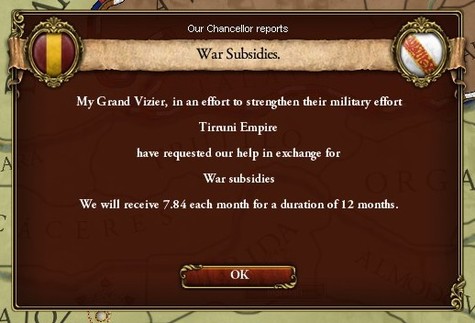

The Emperor, upon hearing of the disastrous battle of Tulaytullah, agreed to temporarily increase the subsidies he was supplying to the Majlis.

Putting this new influx of money to good use, Raed then gave orders to begin rebuilding the army (again), only for more bad news to arrive before the year was out.

Early in December of 1827, Tulaytullah - despite its massive garrison and reinforced walls - collapsed before the Moroccan onslaught in what could only be an act of treachery. Despite help from the inside, the Berbers subjected Tulaytullah to the usual brutalities, carrying off priceless statues and artefacts as they plundered their way through the city.

And of course, the surrounding countryside quickly followed, with nearby towns and cities surrendering in futile attempts to avoid being sacked. Another blow arrived early in 1828, as al-Mansha also opened its gates to the Almoravid army, handing over a vital fortress with scarcely a bullet fired.

Fortunately, however, that was as far as the Berbers were willing to go. With a toehold in al-Andalus firmly established, the Almoravid army turned around and began marching northward, launching another spectacular offensive deep into Catalonia and the Tirruni Empire.

Moving to the east, however, February of 1828 brought another declaration of war with it. King Apanoub of Crusader Egypt, desperate to repair his image and regain his lost prestige, had sent his armies flooding into Vakhtani-occupied Syria.

As was quickly becoming usual, however, this would prove to be another ill-timed and foolish decision from the young king. The Vakhtani Caliph already had half of his empire mobilised, so it didn’t take much to overwhelm the Egyptian invaders, forcing them to retreat before launching a series of raids into Damascus.

That said, fighting on two different fronts in two different wars would soon take its toll, and it wasn’t long before the overextended Vakhtani army began to suffer defeats on the battlefield. Not only were the Serbians already pushing deep into Anatolia, but the Armenians also suffered a stinging defeat to the Egyptians in the battle of Beirut, forcing them to abandon Syria altogether.

By the summer of 1828, any hopes of ending the war on their terms would be long forgotten. The Serbs were approaching from the west and the Egyptians from the south, and though the Vakhtanis fought bitterly for every inch of lost soil, only the Armenian heartland would still be under the Caliph’s rule by summer’s end.

And as though that weren’t enough, the advancing armies also prompted thousands of rioters and insurgents to rise up throughout Anatolia, with the most prominent being a series of revolutionary rebellions in Armenia-Proper. With the Vakhtani army now a shell of its former self, dozens of cities quickly fell to these so-called traitors and anarchists, with the Vakhtani Caliph now controlling little more than his capital.

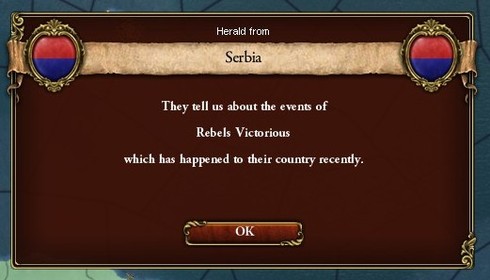

Unfortunately for the invaders, however, their home situation was little better. The Egyptians suppressed their usual Muslim uprisings easily enough, but the Serbs were facing a full-blown civil war in the Balkans, one that they undoubtedly losing. Led primarily by the Bulgarians, the rebels had engaged in protracted guerrilla warfare against the Serbian armies, avoiding pitched battles and instead relying on hit-and-run tactics.

And with the vast majority of Serbian resources already devoted to the war in Anatolia, these tactics would prove to be a resounding success, with the armies sent against the rebels slowly being bled dry and picked off, one by one.

By September of that year, the rebels and revolutionaries finally agreed to a temporary truce, with the borders of two new countries firmly established in the Balkan peninsula. Though raids, forays and assaults were still commonplace, many would later regard this as the rebirth of Bulgaria and Wallachia, independent at long last.

Further north, meanwhile, the War of Russian Leadership had resumed with its characteristic ferocity and barbarity. There would be no stalemate this time, however, with the Smolenskian army crushing the Novgorodian forces in a series of bloody battles. Before the end of the year, they had half of Russia proper under occupation, turning the war decisively in their favour.

Moving back to the west, meanwhile, the Almoravid siege of Barshaluna had come to a successful end. There were dozens of ships blockading it at sea and a hundred thousand Berbers surrounding it on land, so there was little chance of repelling the besiegers, with a handful of attempted sorties all failing miserably. The gates of Barshaluna were breached within two months, with the Berber-Indian army pouring through them like a mass of locusts, burning and killing indiscriminately.

With Barshaluna captured, the road to Narbuna - the grand capital of the Tirruni Empire - now stood wide open. Wasting no time at all, the Moroccan army was force-marched towards the city, determined to land another stinging blow on Tirruni and his perceived invulnerability.

When the curtain-walls of Narbuna came into sight, however, there was already a 25000-strong Tirruni army camping beneath them. Still wary despite by their recent victories, the Berbers were careful to surround the enemy army in all directions before engaging them, and slaughtering them to a man in a decisive victory. With half the army dead and the other half in chains, the Berbers finally turned on the Tirruni capital, beginning the year-long siege of Narbuna.

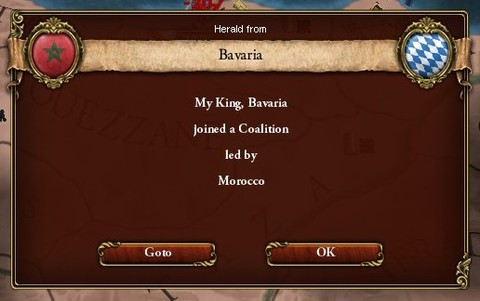

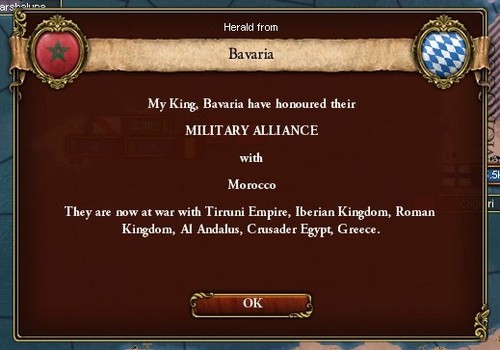

Even as artillery began blowing at the walls of Narbuna, however, high-ranking Moroccan ambassadors were meeting with foreign diplomats all across Europe. And after a series of discussions and negotiations, they managed to score a massive diplomatic victory, convincing the German powers of Hannover and Bavaria to join the Almoravid coalition.

Promising them seats in the post-war conference that would redraw Europe, the Almoravid Sultan Yahya personally announced their entry into the war in October of 1827.

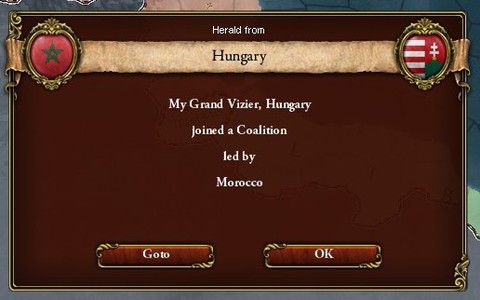

And the Almoravid successes didn’t end there, as yet another kingdom was coerced into joining their pact late into 1827. Hungary, the absolutist bastion bordering on Revolutionary Serbia, agreed to join the Almoravid Coalition in exchange for military assistance against the revolutionary threat, which the Moroccans were quick to agree to.

Thus, by January of 1828, Sahim Tirruni had three new enemies to deal with to his north. Wasting no time in joining the struggle, the three powers launched a joint invasion of Italy later that month, with over 100,000 soldiers swarming across Bavaria and into the Tirruni Empire.

Hannover and Bavaria cleverly decided to commit as few troops as possible, at least until the war turned more decisively in their favour. The Hungarians, meanwhile, threw as many men and boys into the offensive as possible, with their total forces amounting to almost 90,000 men - the vast majority of the invading armies.

[img][/img]

Something had to be done, that much was clear, or the Tirruni Empire will have collapsed by the end of the year. Most of Tirruni’s forces - and the emperor himself - were still in southern Italy, attempting and failing to cross into Sicily and finally crush the Jizrunid Emirate.

As word of the siege of Narbuna and the German-Hungarian invasion reached him, however, Emperor Tirruni was forced to abandon his plans for Palermo. Quickly signing a one-sided treaty with Emir Ibrahim, Tirruni rushed north with all his strength, determined to stem the tide of humiliating defeats he’d been suffering these past few months.

Rather than engage the invading Germans and Hungarians, however, Tirruni marched straight through Italy and Occitania. He would deal with the greater threat first - the Moroccans.

After a rushed month-long march, the Tirruni army finally reached Narbuna, where the Berbers were desperately attempting to penetrate the inner walls of the city. Emperor Sahim, grateful to have arrived before the fall of his capital, immediately threw his forces into battle with the Moroccans.

The next two months would consists of a long and bloody series of engagements between the two enemies, with both sides scoring important victories and suffering heavy defeats. The Almoravid army emerged triumphant in early battles, repelling two massive attacks with heavy casualties.

Tirruni refused to abandon his capital, however, he knew that his international prestige would never recover from such a disaster. So he immediately rebuilt his forces and launched another attack, using every trick in the book in hopless attempts to crush the Moroccan army.

The Emperor rarely relied on a single strategy at war, however, and concurrently sent another army to besiege Barshaluna. A string of battles around both Narbuna and Barshaluna followed, and though the Moroccans emerged victorious in the north, Tirruni’s forces were able to overwhelm the Berber garrison and recapture Barshaluna further south.

Even better, the Moroccans foolishly sent large parts of their army south in an attempt to lift the siege, not realising that Barshaluna had already fallen. Upon hearing of these movements, Tirruni launched into a final attack, separately engaging and masterfully crushing the two armies in decisive battles.

With a third of their number dead and another third captured, the Almoravids were finally forced to abandon their offensive into the Tirruni Empire. Falling back with all the haste they could manage, the Berbers retreated to their captured territories in al-Andalus, which remained largely intact. The Andalusi had managed to recaptured al-Mansha whilst the Moroccans were campaigning in Catalonia, and even besiege Tulaytullah for a short spell, only to abandon it as they retreated.

Before long, it became apparent that the Almoravid army was being escorted back to Africa, with almost ten thousand men loaded onto ships in the Valencia harbours within days. Determined to gain a victory, any victory at all, Sheikh Fadhil launched northwards on an unauthorised offensive against the Moroccan army.

Now numbering just 15000, the Berbers were forced to flee Valencia as the Andalusi approached, only to be pinned down a few miles north of the city.

Outnumbered and surrounded, a largely one-sided but very bloody battle followed, with the Berber army decisively crushed within hours of the fighting breaking out. Finally unleashing their pent-up anger and aggression, Sheikh Fadhil left the Majlisi Guard to murder and torture without restriction, with thousands of Berbers and Indians suffering humiliating deaths long after the battle had been decided.

The noble-born commander then marched on Tulaytullah, where the small garrison was similarly massacred before the remaining defenders opened the gates to the Andalusi army, foolishly hoping that their lives would be spared. Once the city was firmly under Andalusi control, huge celebrations erupted throughout Tulaytullah, with all the revelry and debauchery led by the victorious sheikh Fadhil himself.

After a few days spent drinking and whoring to his heart’s content, sheikh Fadhil managed to gather his wits again, leaving Tulaytullah with his army behind him. The commander marched on Qartayannat, where the Almoravid offensive had begun almost two years ago, and quickly had the fortress surrounded on land. After a few attempts to starve it out failed, the Andalusi launched a series of assaults on its walls, finally recapturing the fortress late in April.

More good news arrived a few days later, with Sahim Tirruni crushing the remnants of the Almoravid army and recapturing Valencia. Once the city was secured, the Emperor personally addressed the flocking masses in an impassioned speech, where he finally proclaimed that the Almoravid Offensive had come to its inevitable, humiliating end.

Celebrations broke out all across al-Andalus, but the joyous mood in Qadis quickly soured upon the arrival of diplomats from Tirruni. With Iberia secure once more, the Emperor had seen it fit to slash the monetary subsidies he was supplying the Majlis al-Shura, with Grand Vizier Zulfiqar very nearly suffering another stroke when being given the news.

But Sahim Tirruni, Sultan of Sultans and Emperor of Europe, didn’t care much for the anger of Zulfiqar. Ignoring the angry protestations coming from Qadis, he instead devoted his energy to repelling the German-Hungarian invasion of Italy, sending his armies to meet them just as they besieged Pisa.

The Hannoverian army managed to stand its own, but both the Hungarians and Bavarians faltered on the battlefield, with large parts of the Hungarian army slaughtered in a series of disastrous engagements throughout May. After suffering tens of thousands of casualties, the King of Hungary finally agreed to bow out of the war, agreeing to never again join the Almoravids in alliance.

Now facing only the Germans, Tirruni was able to slowly push them back from Italy, recapturing Parma and Milan as he did so. Once they reached the Alps, however, the Hannoverian army was able to counter-attack and repel Tirruni’s forces, using the natural defensive terrain to great advantage. The next few weeks were spent in low-intensity warfare, with Tirruni sending several small militias to dislodge the Germans, and the Germans repulsing each of them without much difficulty.

For the moment, at least, the Tirruni-German war was at a stalemate.

So as Tirruni began drawing on the last of his manpower reserves to build up new armies, the war entered another lull, though this would prove to be much shorter than the last. The Almoravids, desperate to regain the initiative, launched a series of naval invasions into Italy and Occitania. Personally led by their emperor, the Tirruni army defeated most of them easily enough, though the Berbers managed to gain a foothold in southern Italy.

Back in Iberia, meanwhile, everything was about to change.

With Almoravid naval power concentrated in the Mediterranean, the straits of Gibraltar were guarded by a mere token force, presenting a unique opportunity to the admiralty of al-Andalus. The army and navy were both becoming increasingly autonomous, and the Grand Admiral - tired of his plans and operations being postponed by Zulfiqar - decided to seize on this opportunity without even consulting the Grand Vizier on the matter.

So after preliminary scouting missions, which confirmed that there were only ten Almoravid vessels patrolling the straits, Admiral Sayf al-Talasi struck south with the entire strength of his navy.

The naval engagement that followed was the first initiated by the Andalusi in decades, if not longer. With cannonry blasting wood and metal apart, thousands of sailors gunned down or drowned, and entire ships sent up in flames, the battle was much bloodier than many had expected.

The naval reforms in recent years had paid off, however, and after suffering two sunken warships (including an expensive ship-of-the-line), the small Moroccan fleet was forced to abandon the fight and fall back.

And all of the sudden, after years of planning and praying, the straits stood empty.

Wasting no time at all, Sayf al-Talasi sent word of his victory to Sheikh Fadhil al-Farihi, who was now in complete command of the Majlisi Guard. As the sheikh rushed south with his forces, the Grand Admiral also summoned every transport vessel he could get his hands on, with the entire navy meeting at the harbours of Qadis just days later.

As much of the Majlisi Guard was loaded onto transports as possible, but even as the navy began its passage across the straits, word reached the Grand Admiral of more Almoravid warships approaching. Thus, forced to make a split-second decision, Admiral Sayf sent the transports ahead without an escort of any kind. If they met an enemy whilst they sailed southward, then they’d be caught defenceless, with the army sure to be sunk in its entirety.

The Andalusi Navy, meanwhile, halted and prepared to engage the advancing Moroccan fleet.

The warships clashed just hours later, beginning one of the largest naval engagements of the Tirruni Wars. The early hours of the battle were largely one-sided, with the numerically-superior Andalusi easily surrounding the enemy fleet, sinking a large frigate after two hours of heavy gunfire.

It wasn’t long before reinforcements arrived, however. More specifically, another twelve Moroccan ship-of-the-lines, all triple-decked and armed with long rows of gunnery, and all manned by far more proficient sailors than the Andalusi. As would quickly become apparent, this was more than enough to shift the advantage back to the enemy.

All the same, Sayf al-Talasi refused to surrender or retreat, doing everything he could to keep the Berbers from advancing past him. He would hold the line, even if it cost him every ship he had.

And Sayf’s naval ingenuity, for all his inexperience, was second to none. After an entire day of heavy fighting, he finally caught sight of Andalusi transports, making their way back across the straits on their return trip. This was all that Sayf needed, with the Grand Admiral suddenly breaking away from the battle and leading a desperate retreat back to Qadis, sending the city up in celebration upon his arrival.

Why?

Because, whilst he had undoubtedly lost the battle of the straits, the Grand Admiral had scored a far more important victory on another front. His navy had suffered heavy damages, his ship-of-the-lines were all in desperate need of repairs, his battered frigates and second-rates were on the verge of falling apart. But he was victorious, all the same, and earnestly joined in the frivolous festivities.

Almost a hundred miles south of Qadis, the Majlisi Guard touched down on Moroccan sands, quickly storming and capturing a nearby castle. Just a few months ago, the Andalusi were firmly on the defensive, losing battles and cities to the Berbers, desperately relying on aid from Tirruni just to stay afloat. Many had believed that Andalusia’s revival was already at an end, with Iberia fated to be nothing more than a puppet, resigned to Almoravid imperialism.

Now, however, the odds had shifted in their favour. Now, they were the ones on the offensive. And now, the greatest power in the world lay before them, ripe for the taking.

World of 1828:

The country name colours represent the in-game coalitions, with red for the Almoravids, yellowish/gold for Tirruni, and white for neutral (even if they're in a separate conflict).